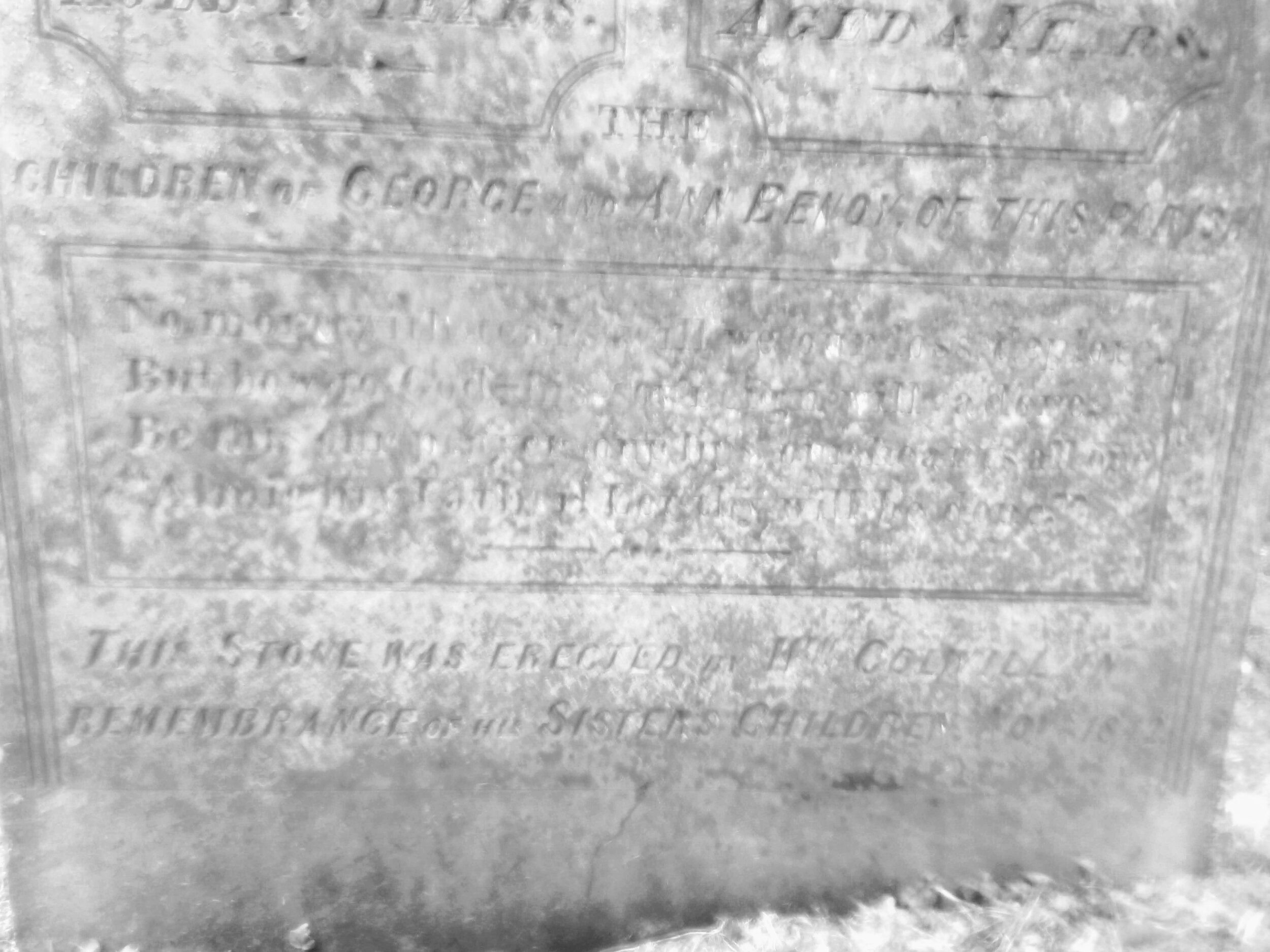

No more with tears

No more with tears will we our loss deplore

But bow to God his sovereign will adore

Be this our prayer our lips our hearts all one

Almighty Father let thy will be done.

One hundred and seventy eight years ago, on 4th September 1842, three children joined their brother in the ground outside the west door to Werrington church, Cornwall. The next day their youngest brother John, just four years old, was buried beside them. Five children in eight days who had all died of cholera. Nearly a whole family wiped out by a then fatal, but later found to be treatable, bacterial disease.

Their mother, Ann Benoy, was beside herself in her wailing lament, bearing a grief unlike any other she had known. On the anniversary of her children's burial, she tells me the story from beyond the veil.

“That week was hell on earth. I couldn’t stop it unfolding. I didn’t sleep for days. Young William had been out in the fields and came home to Grove Town farm with pains in his stomach, sweating, clutching at his sides, vomiting and with the most terrible watery diarrhea coming on. There was mess everywhere. I got him to the bed he shared with his brothers, and had the towels, blankets and a bucket ready. He was suddenly so sickly so quickly and I didn’t know quite what to be doing. He was so weak. My husband George immediately rode the several miles into Launceston to call on the doctor. But by the time they both arrived back, William had gone. In a state of shock, I was holding him in my arms. The blue tinge to his skin matched the blue of my best Sunday summer dress.

“We’d not seen anything quite like this illness in the village. A sickness spreading so fast and so virulent. Two days later the other children were showing the same symptoms. I felt so helpless and could only sit by their sides, holding them, rocking them, trying my best to soothe them as any mother would. There was no time for immediate grief, I was just coping with the initial shock and praying my young ones would live. The doctor had said it was likely to be cholera, a disease carried in the air by putrid smells, and that we should close all the windows, cover our faces with veils, and burn clove oil. I’d heard too from a neighbour that it was poison from the soil. By the end of the week, the whole farmhouse was in mourning, the tears weeping down its walls flowing as fast as the Tamar. All the little ones laid out together. All blue in the face. My precious blue angels.

“The vicar had muttered something about divine retribution for our sins, and now my darlings had found peace with God. In my heart, I knew we had not sinned. Generations of hard working farmers toiling the land at Werrington, ever since grandfather Isaac Benoy, born at Egloskerry in 1635 of Huguenot refugees, had settled in the parish. His bones lay in the ground at the old medieval church of St Martins, before it was knocked down to make way for the big house extensions. They say the villagers had been up in arms but there was nothing that could be done to stop the demolition despite the protests from families whose generations were in the ground there. It felt like a desecration by the rich and powerful. Yes, the old church had fallen into disrepair during the fierce fighting that took place on the estate during the Civil War but it was still loved by the parishioners.

“In my mind, the real sinners were the nobility up at the Hall. The family of slave traders, rakes, Hellfire Club founders and the fraudsters that had built Werrington Hall on their ill-gotten gains. But there was no stopping them. The replacement church was built in its new location in 1742. One hundred years later, five of my seven children were lowered gently into its holy earth.

“I could hardly stand as my brother and both my Georges, husband and eldest son, alongside our village neighbours, carried their small coffins across the fields and lanes to the church for their funerals. I can barely remember the details of those awful days, yet I can so remember the patchwork of colour against the grain of the wood. I wanted to bury myself alive in their graves. Climb in with them and curl myself around their wooden boxes and not let go. I wanted to eat the soil into which they had been set. Rip off my dress and rub the red earth deep into the folds of my skin. How could I leave them, their small fragile bodies, cold and alone in the dark?

“As the autumn nights drew in, I entered a deep depression, ever fearful that baby Ann would be the next to be taken from me. She was only four months old when her brothers and sisters fell sick. It was a miracle she did not succumb - I was managing to breastfeed her, my milk still came at 40. It was her small life that somehow kept me going. Although the Lord did eventually claim her, but not until she was seventeen. Why did he want all my children before me?

“There was no joy at Grove Town that winter. The stone walls felt thick, cold, and heavy. I could not face talking to stonemasons Bounsall and Lanson to arrange their headstones. My brother William kindly took care of that - the dear-of-him.

“I shed so many tears. Brother William urged me to look ahead to the future as he held my hand and told me of the beautiful headstones in the Western corner of the churchyard that the masons had erected. What future? For a long time I could not bring myself to visit, certain that if I did, I would break into a myriad of tiny pieces never to be put back together again. William told me how the community and my family would remember them for years to come. They would not be forgotten. I knew the twelve stone apostles set into the walls of St Martin’s were forever crying for my five innocents. I saw those statues weep with my own eyes. By Spring and the stirring of new life on the land, I resolved to let them cry my tears for me. Instead, I would simply listen for the laughter of William, Thomazin, Thomas, Jane, and John carried on the wind in high summer across the green fields and Cornish hedgerows. I would hold them close in my heart until the time came when I would be with them once again.

“Several years later, I heard that a doctor in London had identified that contaminated food or water was how cholera was spread, and that he learned how to treat it. Good sanitation and access to clean water were key. We never did locate the source of our Werrington farm outbreak.”

Here lie the remains of William Benoy who died August 28th 1842, aged 14 years Thomas Benoy who died September 1st 1842, aged 8 years Thomazin Benoy who died September 2nd 1842, aged 11 years Jane Benoy who died September 3rd 1842, aged 16 years John Benoy who died September 4th 1842, aged 4 years The children of George and Ann Benoy of this parish No more with tears will we our loss deplore But bow to God his sovereign will adore Be this our prayer our lips our hearts all one Almighty Father let thy will be done. This stone was erected by William Colwill in remembrance of his sister’s children November 1842

In 1871, George and Mary Benoy were living at Grove Town Cottage - no longer at the main farm house. George was listed in the census as a pauper agricultural labourer, aged 74. By the time of their deaths they had outlived six of their seven children and had lost everything. Ann died in November 1872 - thirty years after she had buried her five children. They are my second cousins x6 on my maternal great grandmother’s line.

On a late August wet, grey day, these children's graves were the first that I walked towards as I entered the church grounds. As I dropped to my knees, knowing intuitively that they were my cousins, the heavens opened and the sky cried tears of joy and sadness at this ancestral homecoming.

The cholera epidemics in nineteenth century Britain

It was only ten years before my cousins died, that the first pandemic of cholera arrived on British shores. An ancient disease of the Ganges Delta, it spread with the advent of increased trade and colonisation across the continent and into Europe. In 1831, the cholera landed ashore in Sunderland with sailors aboard a sailing ship. As it began to spread, ships were ordered to quarantine before landing ashore. Many local authorities ignored the directive. The disease spread and took hold in areas of overcrowding or poor sanitation. Lack of understanding of how it was spread, the many conspiracy theories, and resistance to attempts to stop it spreading with limited knowledge available at the time, caused thousands of deaths across the country. The big medical and public health breakthrough came in London in 1851, with Dr John Snow and his observations around the Soho water pump on Broad Street, in a crowded part of London.

Cholera still exists today and outbreaks occur around the world where sanitation is poor, and WHO is pledged to eradicate it. Treatment is available, and the key to success is rapid rehydration with oral rehydration fluids, basically sugar water, along with antibiotics in the most severe cases. A patient with cholera should never die if they can get to a treatment center in time. There are also three vaccines that can be administered in areas where cholera is endemic or when an epidemic begins to spread. More than 30 million people have been immunized since the oral vaccines were developed in the late 1980s.