Absolute Pardon: Margaret Butter and the 1661 Witch Trials of Prestonpans

Margaret Butter, Medicine Spoon Memorial Embroidery, 17 November 2020

Butter Witch

Butter,

soft and smooth in my mouth

soothing the stench of burned flesh

still stuck in my craw,

a balm for the witch wounds

of Prestonpans.

Fresh cream turned sour,

churned with the

tears of 1000 women crossed

across Scotland.

Old, lonely, widowed, strange,

with their dark haired cats

melting gold on a silver spoon,

medicine to swallow down

the bitter herbs of betrayal

by neighbours at dawn.

Butter, her red heart

beats on the black cross

of the stake.

My mother took me

to watch Margaret in the square,

an afternoon out,

a warning not to become

mixed up with edge dwelling women.

I was six,

I could hear their screams

in my dream time.

I was frightened in my night sweated

gown, white strips of rag in my hair

knotted with pricks of steel pin fingers

looking for my makers mark,

the burn of the Devil.

The butter witch

who wouldn't fully melt in my mouth,

a throat choked until pardoned.

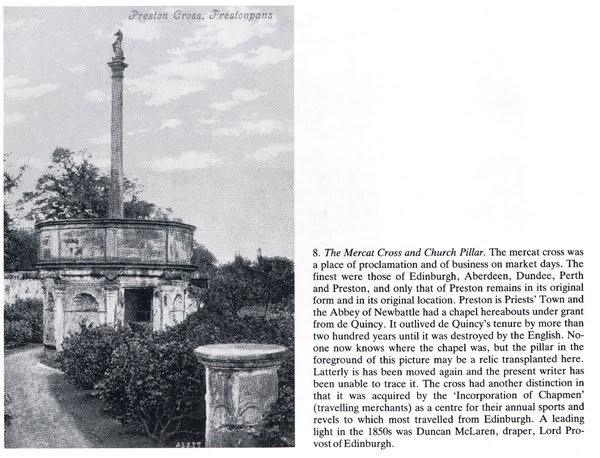

It is 1661 in Prestonpans, a village formerly known as Saltpans, along the coast from Musselburgh, in East Lothian, Scotland. Not so far from Edinburgh. A coastal town famed for its manufacture of salt from sea water in great boiling copper cauldrons. The fires stoked by the coal from the nearby mines. Barbara Foster was six years old. The village elders had been building a pyre in the market square where she would sometimes play with her doll and skipping rope. It was the long, hot summer of the witch trials. As hot as it would ever get on that North Sea coast where Baltic winds would blow in to bite the tongue of even the most hardened bitter gossip. That year the talk was again rife on the lips of the townsfolk, about the older women who had been accused in this second wave of persecution to drive out the Devil. As the elders said, the Devil walked amongst them and those that invited him in to their home must be dealt with and exposed.

Barbara’s mother was tying on her bonnet. Deep down she didn’t want to go and watch the spectacle, but it was expected. She saw the pyre being built, the wooden stake going up, the chair in which the women would be strapped, strangled and then tied to the stake half conscious, fading in and out of lucidity. This was the world she had brought her daughter into; her sensitive, almost otherworldly child. Barbara could feel the growing anxiety in her own mother; she could feel the anxiety in her sisters; she could feel the tension in Prestonpans as the fire was stoked. Sometimes, in the night she could hear the screams of the women as their interrogators were pricking them to find the Devil’s mark; as they were tearing off their fingernails, piercing the flesh beneath to find the numb spot which proved they were in league with Satan. Barbara could hear their screams in her dreams and she would cling to her doll ever more tightly.

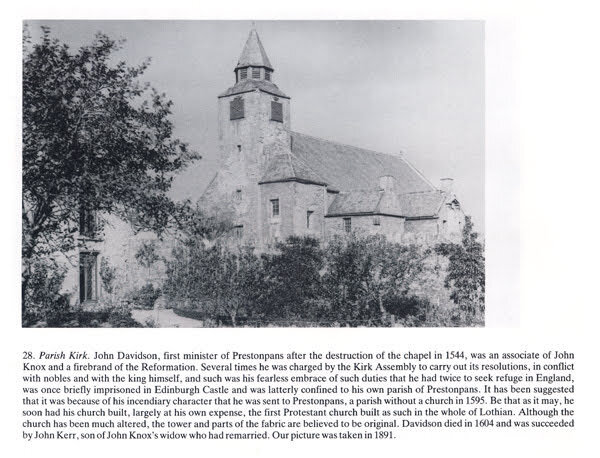

As the crowds began to gather, Barbara saw a dark haired boy, who looked about ten or eleven, dart across the square. She knew him vaguely from her father’s friend and fellow church elder, John Banks. This boy was John Banks Jnr. She had seen him in church, the very same kirk that had been founded and substantially paid for by John Davidson, that awkward rebel priest and Presbyterian reforming thorn in the side of King James IV of Scotland (1st of England). John Davidson, the first priest of the new kirk of Prestonpans. He had arrived in the village in 1594, just after the first witch trials had swept through in 1590 on the back of the great storm that disrupted the King's voyage to meet his new Queen, Anne of Denmark. A storm that the first wave of witch women had been accused of invoking by drowning a cat in a black magic Satanic rite. Those women were tried and executed.

John Davidson was dogmatic and strict in his devotion to the Lord. However, both Barbara and John's grandfathers had welcomed him with open arms. After 50 years without a parish church, they were glad of this force riding in on the winds to drive out the Devil from the villagers in the surrounding hamlets. Those that were want to drink and cuss, fight and fornicate without a care for the Good Lord. This behaviour was clearly the Devil’s work without a kirk to contain him. The winds of change were indeed blowing hard. John Davidson had the ear of the King, a man who loved to personally take part in the torture of these woman accused of dancing with the Devil on the Sabbath, spinning with him anticlockwise to unwind their baptism. A King who took a personal interest in the so-called witchcraft of women. Crafts he did not understand, that he wanted to stamp out to assure his total power and the subjugation of his people both in Scotland and now in England.

That afternoon three women were to be burned. Three women in their fifties; Margaret with flecks of grey in her hair. Married in 1635, now a widow. A healer and a herbalist, many local women would go to her for help. Barbara's mother visited when she was pregnant and in pain. She took her herbal medicine. Margaret never remarried after her husband died, even though she had offers. She preferred to live alone with the freedom that brought. She was accused as a witch by another woman who had also been imprisoned, tortured and tried. The commissioners sent their henchmen to beat down the door of her cottage near the edge of the black coal hills overlooking the salt pans. They found Margaret simply busy minding her own business, drying herbs on her range, a large pan bubbling on the stove brewing a remedy for the livers of those who had been drinking too much again in the village.

There in her very own kitchen Margaret was seized and dragged outside by her hair, thrown into irons and taken by cart to the town hall. That night and for many subsequent night she endured grave brutalities to prove she was indeed dancing with the Devil, making her neighbours sin and turn to drink. She was imprisoned for weeks, deprived of sleep, waiting for the sentence to be delivered. Eventually it came on that fateful summer's afternoon. Margaret was thrust into the square, strapped to the wooden chair set by the pyre and garotted, so that her voice could cry out no more. When she first passed out she was taken out of the chair and tied to the black stake. Her dirty white gown ripped from her, blood stained over her heart and breasts from the beatings and prickings she had endured. She was tied to the cross by John Banks senior who stepped forward, crying out for the Lord to deliver them from the evil in front of them as he lit the fire. The flames quickly took hold as they leapt up to lick and kiss Margaret’s broken feet. Further proof she was a witch. The smell of her burning flesh soon became overpowering. As the crowd started coughing, Barbara hid her face behind her mothers apron. Her mother scolded her: “Look hard at Margaret and be afraid, so that this fate never befalls you. Live a righteous life my child and forever hold your tongue, lest it be cut out.”

Barbara’s night terrors continued for the rest of her life. For generations afterwards, whole families never fully recovered from the Scottish witch wounds inflicted by these miscarriages of justice. Barbara Foster was my eigth great grandmother who married John Banks Jnr. She told her son Alexander Banks and his wife Marion never to visit the edge of the village, never to speak out against the kirk or their elders. The witchhunt carried on sporadically into the 1700s. Fears began to abate as times changed, until one day a child was born of that East Lothian line in January 1873 in Bridgeton, Glasgow. Mary Robbie, my great grandmother. When she married John ‘Black Jack’ Mitchell, she still carried the witch wound of Prestonpans, the witch wound of betrayal. She was to be betrayed countless times by her husband with his fearsome temper, his drinking and his gambling, a man she felt loved his horses more than her.

In 2004, the Barons Courts of Prestonpans officially pronounced an absolute pardon of the 81 women and men who had suffered miscarriages of justice in the Scottish Witch Hunts. Margaret was one of those named. The last Scottish woman to be tried and imprisoned for witchcraft was in Portsmouth, my hometown, in 1944. That’s just 76 years ago. Helen Duncan was accused of giving away military secrets during a seance!

We arrive now in 2020, in the midst of a global pandemic where hysteria, finger pointing, blame, control and conspiracy theories are rife. An era of fake news, claims and counterclaims, deep community divisions polarised by social media, gossip and rabbit holes forming rich breeding grounds for neighbour to turn upon neighbour. We need to keep vigilante.

Inspired by friends who were taking part in the Medicine Spoon Memorial textile project to commemorate those women who were persecuted as witches, I applied and was sent a spoon to embroider and the name of a woman, Margaret Butter. Instinctively, I immediately felt drawn to create her spoon in the colours of alchemy, black, red, white and gold, stirring a red hearted spoon in a green medicinal chalice or cauldron. This was before I found out that the Butter coats of arms are four red hearts on a white shield with a black cross. This was before I knew that she was from Prestonpans and its history. On 17 November, the very day I finished the embroidery, I made the discovery that my own direct ancestors were from Prestonpans at the time of the witch trials in 1661 and before. Perhaps they too were asking for final forgiveness for the wounds which they inflicted on the women of the village through their connections to the Kirk and its founder.

So we draw the thread and cast off the knot as we spin the ring of the Witches Reel.

Further reading

81 Witches of Prestonpans by Annemarie Allen

Panic and Persecution: Witch-Hunting in East Lothian, 1628-1631