Witchery Tricks - The Murder of Elizabeth Bradwell, Great Yarmouth, 1645

Elizabeth Bradwell, Yarmouth, 1645, medicine spoon embroidery panel

The story of her miscarriage of justice during the East Anglian witch trials as told in her own words

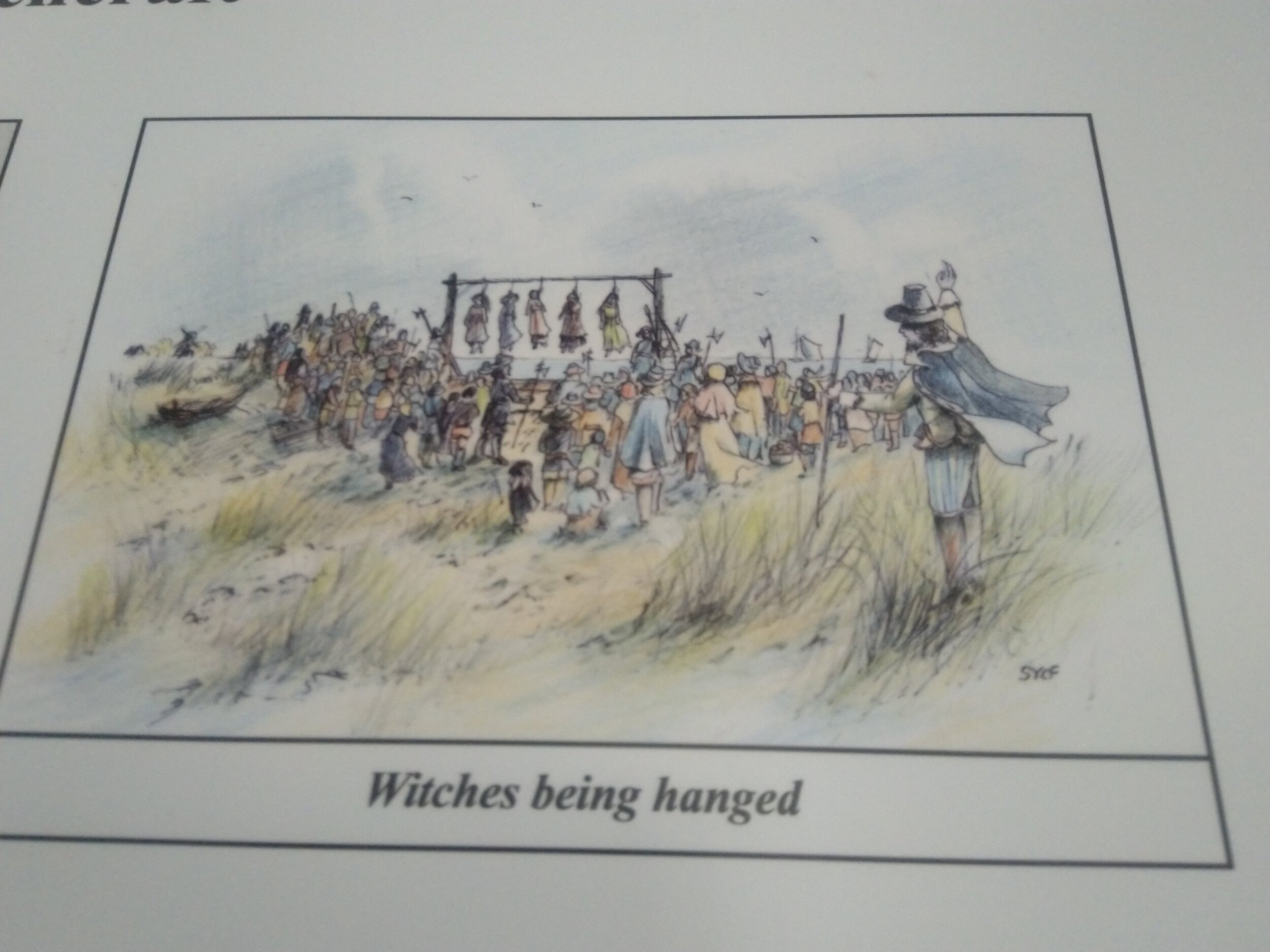

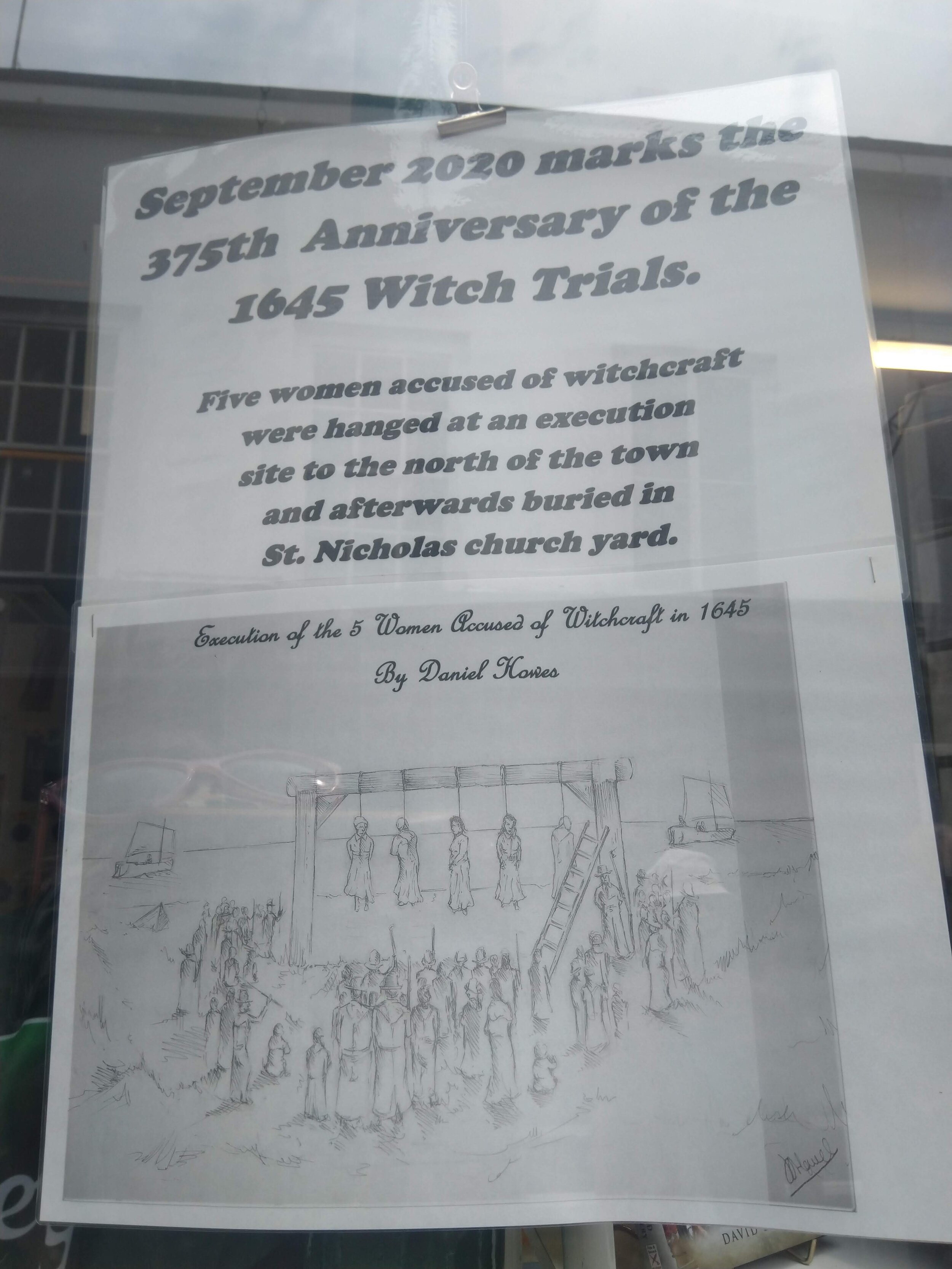

I’m hovering over a memorial spoon embroidery stitched in my name. It is laid out on the grass close to where I am buried on the north side of St Nicholas churchyard in Great Yarmouth. There is no marker for the grave which I share with Alice Clesswell, Bridgit Howard, Maria Blackborne, and Elizabeth Dudgeon. The ground was dug after our bodies were taken down from the gallows, piled in the troll cart and brought back into town. We were hung together as witches on 29 September 1645 and buried the same day. No one wanted to leave five witches on the gallows any longer than necessary. We might just come back to life with the Devil in tow to wreak vengeance on the perpetrators.

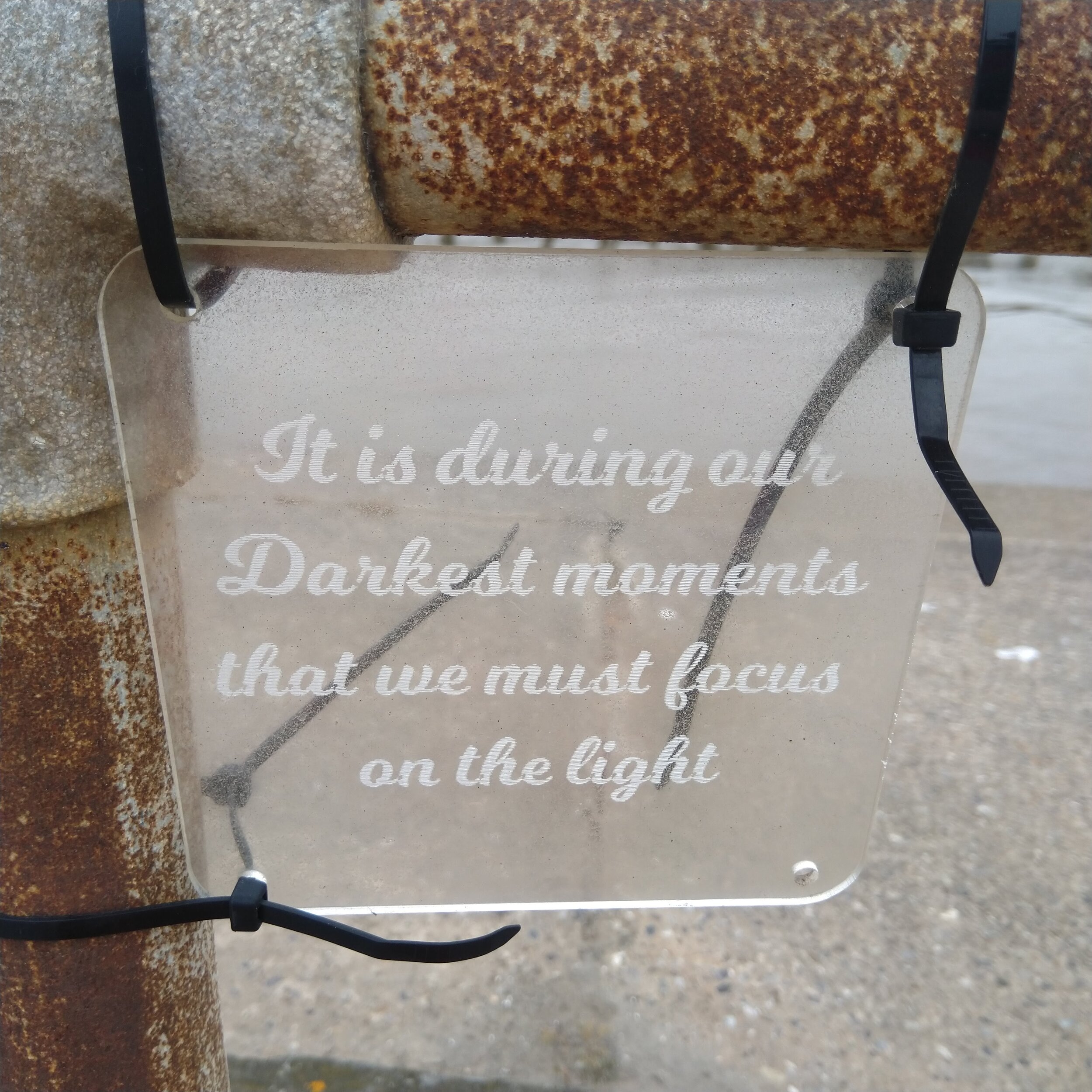

I am here watching this small memorial ceremony created as part of one woman’s pilgrimage to remember me. I’m as famous now as those who brought me here. I’m certainly remembered with more love and compassion than I had ever experienced in my own physical lifetime. I am moved to tears. I feel the weight of centuries falling away. I am light and I am young again.

In the 376 years since I was murdered alongside my ‘witch sisters’ in front of the jeering crowd gathered near what is now the racecourse on the Jellicoe Road, at the edge of the Yarmouth - Caister border, I ask myself - how much has really changed?

It’s true we don't hang people in Britain anymore. The last woman executed was Ruth Ellis in 1955 for shooting dead her abusive boyfriend in a crime of passion. That was only 66 years ago, well within living memory. But when I look at Britain and societies across the world today, I see the same patriarchal patterns of violence played out, simply wearing a different cloak. Violence against women and girls is as endemic as it has ever been.

The term witch hunt has long since entered common speech since those days we were hung or burned in our tens of thousands across Scotland, England, and Europe. It's a term so often appropriated by politicians and those in the media. Only last night I heard an 85-year-old film director explain that the reason he left a political party was because he was being persecuted for the company he kept. “It was a witch hunt”, he said. Not quite, I think. No one is being tortured or killed on the grounds of false confessions and vindictive accusations by their neighbours. Let’s not diminish what happened to me and all those women like me. Let us remember that witch killings still take place in some parts of the world. This is a serious business - a matter of life and death.

On the radio, I listen to the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban. These brutal, hard-line fanatics do not believe in equal rights for women; they beat, torture, rape and kill those who step out over the strict lines they have drawn in the sand. They remind me of the some of the fanatical Puritans I knew in my day.

I listen to details unfolding of the horrific murders in Plymouth, Devon. A young man in his early 20s took his licensed gun and shot his mother and four other people including a three-year-old girl at random before turning the gun on himself. I learned that he was full of self-loathing and rage against women. A hatred fuelled by his inability to have a girlfriend and a sexual relationship with a woman. I discovered that there are thousands of men around the world in online chat rooms spreading this hatred of women, who they believe are solely there to serve them and their needs alone. I’m reminded of young Matthew Hopkins, my torturer and one of my murderers. I always suspected him of being a sadistic mysogynist who got his sexual kicks from torturing women accused of witchcraft. I’m sure he would thrive in this ‘incel’ movement.

I hear those legislators in Texas have just passed a new law where women are now denied their rights over their own bodies and reproductive choices to save a potential life that has not yet been born. Yet simultaneously, Texas has also made it even easier to own a gun in a country that is virtually in a civil war with regular mass shootings that are predominantly committed by men. The irony is not lost. America seems to be falling backwards in time to the dark days of the colonies whose Puritan and Separatist settlers brought their fears of women embracing the devil with them.

I’ve come to believe that this twisted force that kills and tortures is a dark and troubled energy that seems to feed primarily off the broken and angry masculine. I’ve had long enough to witness it down through the centuries since my shattered body was thrown into the earth. It’s been going on for millennia. We are tired of being the scapegoats.

It takes more than one person to kill a ‘witch’

In 1645, a young man in his early 20’s, Matthew Hopkins, the self-styled Witchfinder General, started his three-year reign of terror riding around the counties of East Anglia preying on vulnerable women accused of witchcraft. He exploited the petty disputes between fearful neighbours who were living through a nations’ dramatic upheavals of riots, religious conflict, plague outbreaks and civil war. A war that was fought literally on their doorsteps and in their churches. Matthew made good money from his witch killings, sending more than 300 women to their deaths. His horrific actions were part of the wider societal and political forces at play during those times. Neither did he act alone in my murder.

How many people does it take to execute a woman for alleged witchcraft? One, three, nine, twelve, twenty-four or more? Let me tell you my story and the people that featured in it and you can come to your own conclusions.

Edge-dweller

I was just an old, poor, edge-dwelling beggar woman, desperate to find work and hold on to some small sense of self-worth. A woman desperate to put food in her belly and at times to rage with the roaring wind and waves, crying aloud that no one cared. I’d lived on the beach at Yarmouth in the bowels of an upturned boat for as long as I could remember. It hadn’t always been this way. I’d once been a skilled knitter and weaver, engaged to a handsome herring fisherman. The summer we were due to be married, he’d drowned off the coast in a storm and his body was found washed up along the shore at Caister. The sight of his swollen and disfigured flesh filled me with such horror that I vowed I would never fall in love again. The trauma of seeing my lost love like that never really left me. When my poor parents died and I was evicted from the small, stinking Yarmouth Row room that had been my home for so many years, I found shelter in the old abandoned wooden boat hull on the edge of the dunes that gave me a little peace.

I turned it into a simple home. I would scavenge daily for whatever the sea washed up. I boiled crab and sold the cooked meat in the market inside the town walls. Sometimes I’d find old treasures rolled in on the tide from shipwrecks. I’d sing, talk, and swear out loud to myself and scare off the small boys bold enough to throw mud on my door when they came roaming past. I wasn’t afraid of them. I knew they were more scared of me and what they imagined might lie on my kitchen table or in my iron cooking pot. Often it was just the scraps I’d saved for the small blackbird with a bright yellow beak and a clear eye, who would visit every morning and sing to me so sweetly. It was my joy to feed him whatever I had left from my meagre meals. He became so tame that I only had to hold out my palm with food and he’d land on my forearm and peck away, sometimes breaking the skin of my hand, but I didn’t mind. He broke my loneliness and made me feel needed.

When I was out of crumbs and coins and the beach had not offered up any treasures for me to sell, I would cross through the city gates and walk over to the church to ask for alms from Presbyterian Minister Thomas Whitfield - enough for me not to starve. Thomas was quite the firebrand preacher, but he didn’t frighten me. I’d keep knocking on his door and hollering until he’d open. He would press a penny, sometimes a whole shilling into my hand to show that he was the greatest provider to the parish poor, more so than the other ministers in town. I’d sometimes call on my old neighbours in the Rows. They would hurriedly give me a little food to stuff into my apron pocket or fill my jug with buttermilk before shutting the door in my face, rather than invite me in to sit by their fires. I’d take the opportunity to ask around for work. I could still knit stockings, although the arthritis creeping into my hands meant I was much slower than I used to be. My work was still fine enough though.

A church in turmoil

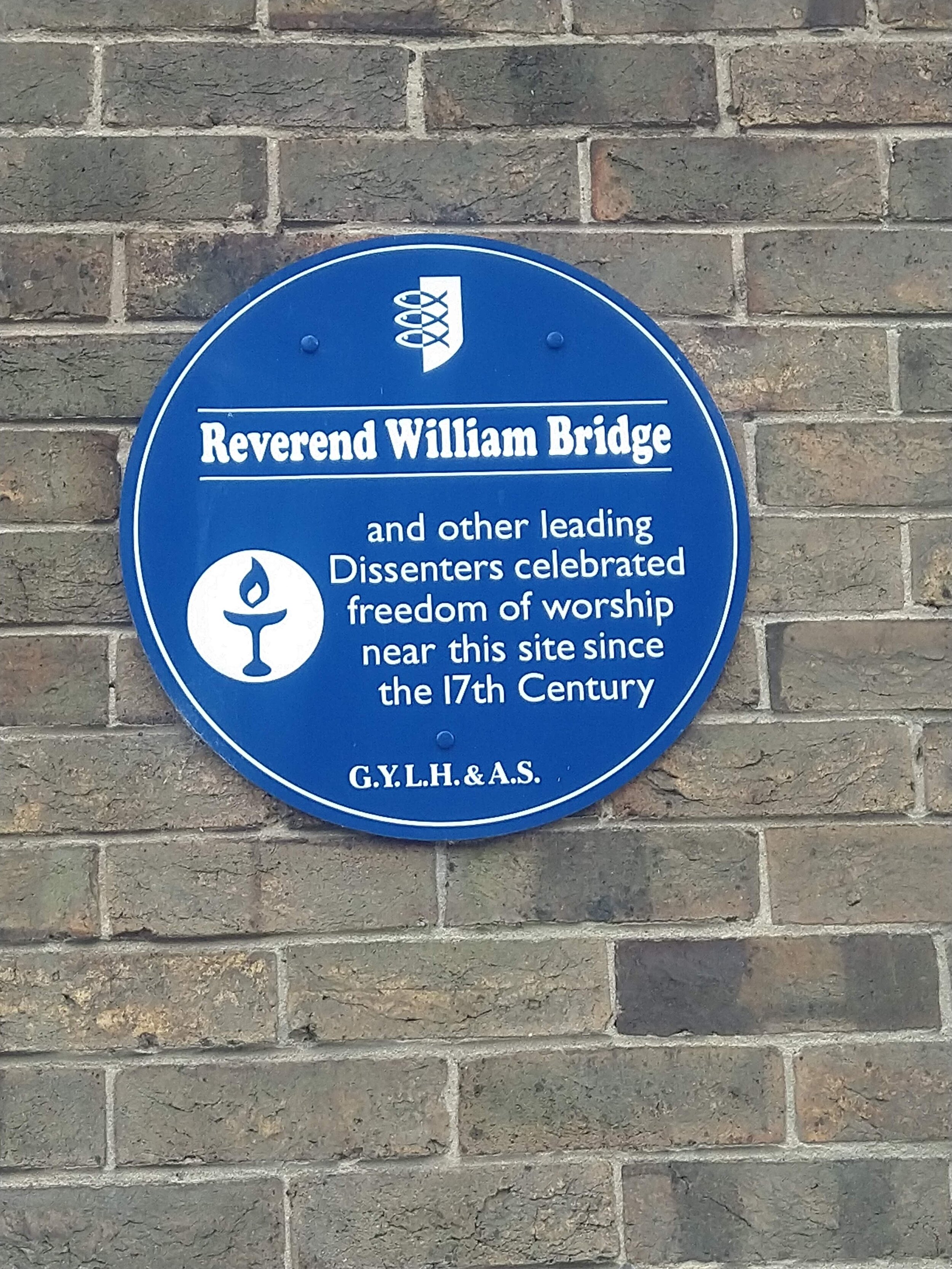

On these trips to church, I’d watch the town’s bigwigs (a forceful breed of Presbyterians and puritan Independent Congregationalists) ignore the old traditional churchgoers led by conformist Minister Matthew Brooks gathering at the South porch, as they made their way round to the north and chancel doors. In 1643, the church had been split into three to accommodate the three warring factions. William Bridges and his puritan Independents had the chance, and Minister Whitfield, the North aisle. They bricked up the beautiful old arches, destroyed the lovely old medieval altar tomb of Thomas Crowmer and even used the north aisle for militia training in wet weather!

Who had to pay for all these alterations and desecrations? The townsfolk. The church factions had been arguing for years about how God should be worshipped and they preached conflicting lectures and sermons. This animosity often spilled out into the churchyard with the ministers shouting at each other in the most ungodly manner, enough to wake the dead. Matthew had no time for the subversive civic puritanism that gripped Yarmouth. In 1627 he had managed to eject John Brinsley, a die-hard puritan lecturer and friend of Minister Whitfield from the town, by order by none other than our King Charles 1st. This had stoked up yet more division.

All I knew was that I had a hunger in my belly that God would not fill however hard I prayed, so I’d tug on the cloak of Henry Moulton (who was a great friend of Minister Whitfield) and beg him for work. If he was in a good mood, he might ask me to go up to his house to be given some knitting. Often, he’d just brush me aside with barely a grunt. So much for their Christian charity.

The cloth merchant and his wife

Henry Moulton, cloth and stocking merchant, town councillor and my occasional employer was my accuser. Against this backdrop of political and religious turmoil in Yarmouth, he served on a corrupt town council that was run like an oligarchy. We were already two years into the civil war, with Yarmouth very much a hotbed of radical and revolutionary activity. Henry had his finger in many pies. However, this devout and influential puritan could not stop his two-year-old son John from falling gravely ill in the winter of 1644/1645 (we were using the old Julian calendar in those days). Henry started looking for someone or something to blame.

Henry’s second wife Bridgit, mother of John and his older brother Thomas, became increasingly convinced that there was something otherworldly about her son’s illness as it progressed. He lay in his cot growing weaker, ever more listless and feverish as winter turned into spring. He did not respond to any of the potions or leeching given to him by the doctor. Bridgit sought the advice of the local goodwife herbalist who was convinced that this was a case of witchcraft. This suspicion was backed up by the household servants who had turned me away that winter evening when I had come knocking for stocking work. In the bitter cold and with hunger still gnawing at my innards, I’d unleashed a barrage of profanities on this rich household that considered themselves to be upstanding religious and charitable reformers yet would not stoop to help an old beggar woman.

The gossip and suspicions about my powers grew more elaborate week by week. By the end of May, Bridgit had heard of a new witchfinder who was having great success routing witches from towns and villages across Essex and Suffolk. She started telling her neighbours that I had placed a curse on her son. What madness! I might holler and swear at the lads who’d come taunting me around my hut or rap the knuckles of those who’d try to steal what little I had to sell at the market, but I would never deliberately hurt a small child. In her desperation, Bridgit kept haranguing Henry to persuade the town council to send word to Matthew Hopkins and his partner John Sterne to examine their son’s case. She prayed daily for a miracle.

Henry was politically ambitious. Besides fearing his son’s imminent death, he could see a campaign to rid the town of the scourge of witchcraft might just be a rallying cry needed to heal the town’s divisions and thus advance his council career. His fellow councillors did not need much persuading. In their puritanical eyes, Yarmouth was clearly full of malevolent witches - they’d already received complaints of 10 others - and must be purged. Finally on 15 August, the town assembly agreed to send word to Master Hopkins, who was already at Bury St Edmunds, to come to town and search for “wicked persons if any be here” in return for a hefty sum. There was quite a bounty on my poor, wretched head and so I was arrested and thrown in the grim and crowded confines of the Tollhouse jail until Hopkins arrived the following month.

The victim and his brother

John Moulton was the main victim of my supposed curse. The second son of Bridgit, he had been sicklying since birth. His brother, five-year-old Thomas was born in 1640 and Bridgit was already stepmother to two older sons aged about 11 and 12 in 1645. With four young boys to care for, one of whom was now seriously ill, and Henry often away for several weeks at a time on business, she was at her wits end not knowing what to do. I wonder now if John may have had meningitis, but back then the disease was not known to doctors.

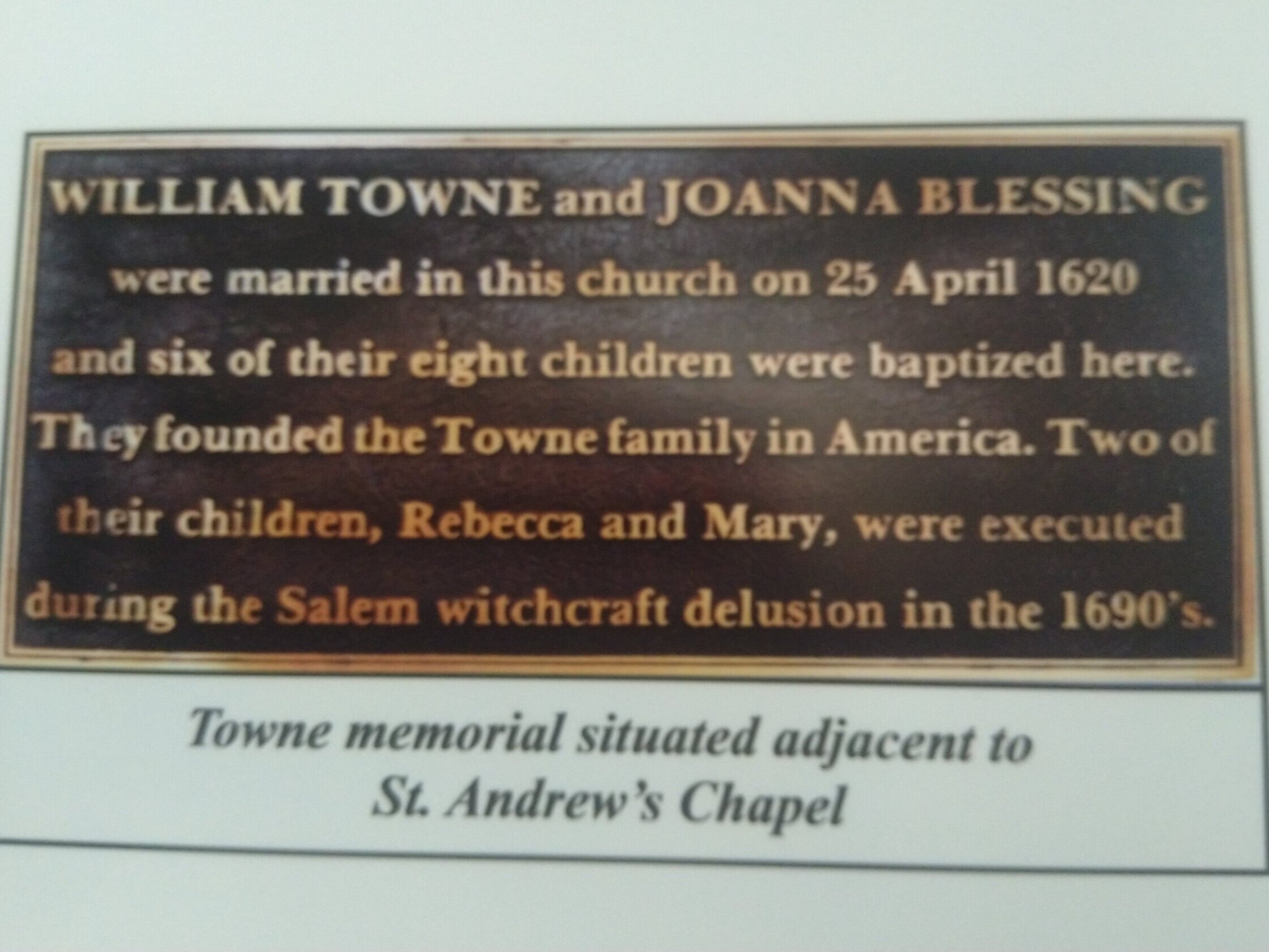

When Henry returned from his travels, Thomas and his older siblings would clamour for attention. As they sat at his knee around the fire, he’d read aloud the letters filled with incredible stories sent from his extended Moulton family members. They had emigrated from Norfolk to America in the 1630s to help build the colonies in New England. I found out later that their Moulton descendants were involved in the Salem witch trials of 1692. Thomas grew up to be a successful baker making biscuits for sailors of the merchant ships and fishing boats. But he never forgot the look I gave him on the day of my execution.

Thomas was one of the last people I saw in the crowd standing before me on the gallows. Clutching at his mother’s apron, his big brown eyes staring in terror from between his fingers, he screamed as I screamed out my curse upon all those that had brought me to my death. Then the hangman strung us up to dangle and jerk and gasp for air. I could see Bridgit clinging on to John, who was by now miraculously healed from his affliction and was violently wriggling in her arms to be let down. Soon they were all screaming as the breath exhaled in one last rattle. The children's screams repeatedly woke the Moulton household with the nightmares they experienced over the weeks that followed my death. They say John’s face was contorted in a frozen expression of horror the day he died a few years before his own father, and not that long after my own death. Brigit didn’t even last the year. She died on 24th October 1645, less than a month after I was buried. She was soon lying cold in the ground not so far from my own rotting body in its cold north facing pit. Henry followed just six years later. Someone had answered my death cry.

Two servants close the door

If only they had been kind to me. It wouldn’t have taken much effort. One pair of stockings to knit was all I asked for. Just one pair. That old manservant was spiteful. He fobbed me off saying he couldn’t give me work on behalf of Master Moulton who was in Amsterdam on business. Yet he acted as though he was master of the house on all other accounts when Henry was away. I thought the young maid would have a softer temperament and give me some work. But she just spat on the ground by my shoe and told me to bugger off. That’s when I suddenly leaned in close and hissed in her face that the Devil would have her guts for garters, before setting off angrily back to my hut. They were both quick to confer that I had placed a curse on the household and especially young Master John.

Two ministers and a goodwife extract a confession

The double-crossing Minister Whitfield was the unholiest man I knew. He begrudgingly gave me alms twice a week when I came knocking on his door. I’m sure it was only to upstage his rival Minister Brooks, not out of real, heartfelt compassion for a lonely, poor old woman like me. He was very quick to volunteer to extract a ‘confession’ out of me and do the Council’s dirty work alongside that preacher friend of his, John Brinsley. They both worked under the advice of demonic torturer Hopkins, who by now was on his way from Bury St Edmunds. Minister Brinsley had only recently wormed his way back into town society under the patronage of Sir John Wentworth after 20 years in exile and had already begun belting out his fire and brimstone lectures in the North aisle of our divided church.

These men kept me awake in the Tollhouse jail for three days and nights, shouting at me, poking at me, making me walk round and round in circles for hours at a time. They fetched Elizabeth Howard, a local midwife who’d do anything to earn a shilling, to strip search me and force me to squat naked on a stool in front of them while they watched me. All the while they were working in shifts to ensure I did not sleep. They were looking for signs of the Devil, or for devilish imps to appear. They gave me only sips of water and an occasional stale biscuit to eat. By the end of the third day, I was so jumbled up, dehydrated and in pain, I had no idea if I was sleeping, waking, or dreaming, let alone what utterances came out of my mouth. I would have said anything just to be left alone on the stinking filthy straw and close my eyes.

Eventually I broke down into many tiny pieces and told them what they wanted to hear, which somehow seemed real at the time. I had made a pact with the Devil. I know now that the truth of my ‘confession’ was recounting a muddled, feverish dream that I’d had on that fateful night after I left Mr Moulton's home in an agitated state. I can’t tell you exactly word for word what my inquisitors forced out of my dry mouth in barely a whisper. But I can share with you those that written down second-hand by Lord Chief Justice Hale many years after my death:

“That Night when she was in Bed, she heard one knock at her Door, and rising to her Window, she saw, it being Moonlight, a tall black Man there; and asking what he would have? He told her that he understood that she was Discontented because she could not get Work, as she expected; and that he would put her into a way that she should never want either Work or anything else. Whereupon she let him in, and asked him what he had then to say to her?

He told her, he must first see her Hand; and then taking out something like a Pen-knife, he gave it a little Scratch, so that Blood followed, and the Mark remained to that time, which she then shewed them; then he took some of the Blood in a Pen, and pulling a Book out of his Pocket, bid her write her Name; and when she said, she could not, he said, he would guide her Hand, and thereupon did so, and wrote her Name in his Book. When this was done, he bid her now ask what she would have: And when she desired first to be revenged of the Man [Henry Moulton’s manservant], he promised to give her an account of it the next Night, and so leaving her some Money, went away for that time.

The next Night he came to her again and told her he could do nothing against the Man; for he went constantly to Church to hear Whitfield and Brinsley and said his Prayers Morning and Evening. Then she desired him to revenge her on the Maid; and he again promised her to give her an account thereof the next Night; but then he said the same of the Maid, and that therefore he could not hurt her. But he said that there was a young Child in the House, which was more easie to be dealt with. Whereupon she desired him to do what he could against it. And the next Night he came again, and brought with him an Image of Wax, and told her they must go and Bury that in the Churchyard, and then the Child which he had put into great pain already should waste and consume away as that Image wasted. Whereupon they went together, and he dug a hole with a Spade which he brought with him, and they Buried it. And when he left her, he bid her whenever she wanted anything, but wish for him to come, and he would presently be with her. “

It was Minister Whitfield’s son that told my ‘confession’ to that despicable and incredibly powerful lawyer Sir Matthew Hale, who wrote it down in his book A Collection of modern relations of matter of fact concerning witches & witchcraft published in London in 1693, nearly 50 years after my death. My story was corrupted in the hands of these powerful and heartless men. Did you know that Lord Hale executed two women for witchcraft and “unnatural” love in 1662? That his judgement in that case was used in the Salem witch trials? Did you know that it was he who said that a married man could not be found guilty of raping his wife, because the wife had automatically given herself to her husband by mutual consent in the marriage contract? So influential was Hale and his writings that this exception to the law of rape existed until 1991, when it was finally repealed by the House of Lords. That’s only 30 years ago!

The Witchfinders – Matthew Hopkins and his assistant John Stearne

After I had made my ‘confession’ Hopkins would still not let me sleep. He told Elizabeth Howard to dress me back into the stinking rags. She mentioned the peck mark scars on my hands from feeding my blackbird, who they interpreted as my ‘familiar’ and evidence that I worked with a devilish imp. I was taken by Hopkins, Whitfield, and Brinsley to the magistrates upstairs at the Tollhouse, who ordered me to be taken straight to Master Moulton’s house to repeat my story in front of the family and then look for the wax effigy I had supposedly buried in the churchyard. This is Justice Hale’s account of what happened:

“The Child having at this time lain in a Languishing condition for about Eighteen Months, and being very near to Death, the Minister sent this Woman with this account to the Magistrates, who thereupon sent her to Mr. Moulton's; where in the same Room where the Child lay almost Dead, she was again Examined concerning the Particulars aforesaid; all which she confessed again, and had no sooner done, but the Child, who was but three Years old, and was thought to be Dead or Dying, Laughed, and began to stir and raise up itself; and from that Instant began to Recover. It was then late in the Night before they had done, so that they could not then search for the Image of Wax but ordered it to be done early the next Morning; and then the Woman being led to the Churchyard, set her Foot upon a certain place, and said, that was the place where it was Buried. But tho they dug and sought for it as well as they could, they could find nothing; whether because it was so wasted, that they lost the relicks of it in the Digging, or removed by the Devil, or whatever else was the reason, it could not be found; but the Child Recovered. This Woman and all the rest were Convicted upon their own Confessions, and were Condemned, and Executed accordingly. They had all their Familiars, and this Woman’s did usually appear in the form of a Black-Bird.”

By August and September 1645, Hopkins and Stearne had already gone along separate roads across East Anglia to cover more ground between them and increase their profits, such was the growing demand for their services during the Civil War. These two men were responsible for killing more women than had been executed in the previous 160 years. There was money to be made in the chaos of civil war and they had convinced themselves their work was necessary.

The torture methods used and overseen by Hopkins and his assistant John Stearne, ten years his senior, were similar in all the cases they were called into investigate. As they were paid to get results, you can see patterns emerging in the confessions they extracted like mine. Making a pact with the Devil who usually appeared as a man and often dressed in black was one, as was having a familiar spirit or imp who appeared as a creature, were features in more than just my case. John Stearne was not present during the three days of torture I endured, but he did write down his second-hand account of my confession which he said was told to him by Matthew Hopkins. This was published in 1648, three years after my death and the year after Matthew Hopkins died. This is what Stearne wrote about my case in his book: A Confirmation and Discovery of Witchcraft, (1648)

"So also by Witches deeds, as when any have seen them with their spirits, or seen to feed some creatures secretly; or where the Witch hath put such, which may be known by the smell of the place; for they will stink detestably, which we have often found true in the time they have been kept, if their Imps or Familiars came to suck in the meantime, as you may finde they often have. Also when it can be found that they have made pictures; as I have credibly heard of one of Yarmouth, who since the aforementioned time suffered there, and confessed that she had made a picture of wax or clay, I do not well remember which, of the proportion of a childe which she was intended to work her mischief against, and had thrust a nail in the head thereof, and so had buried it in a place, which she then confessed; and that as that consumed, so should the childe, and did, a long time, as I was told by Master Hopkins, who was there, and took her Confession, and went to look for the picture; and that the childe (as I have heard) did soon after mend, and grew lusty again. A hellish invention.

And so many such Witchery-tricks, both of this kinde and otherwise, have thus been lately found out: as the giving anything to any man or other creature, which immediately caused either pains or death; as was at Brampford and other places, as you may also finde by their Confessions. So likewise by laying on their hands, or by some one or more fellow-Witches confessing their own Witchcraft, and bearing witnesse against others so as they can make good the truth of their witnesse, and give sufficient proof thereof, as, that they have seen them with their spirits, or that they have received their spirits from them, as beforesaid; or that they can tell when they used their Witchery tricks to do harm, or joyned with them."

After my forced confession at the Moulton’s, the somewhat miraculous and sudden recovery of John Moulton reaffirmed to Hopkins and the council that I was guilty of witchcraft. My trial was set to the 10 September along with the other ten people accused. I wonder now if that servant maid had been slowly poisoning the child with herbs to keep him sedated and prolong his illness, to get me convicted. Perhaps she had stopped once I was imprisoned and so he was able to quickly recover. We shall never know.

Matthew Hopkins was not at my execution, having already moved on to the next town requiring his services but he was one of those I cursed out loud on the gallows. I had nothing to lose. If they believed me to be a witch and were prepared to kill me as a witch, damned if I wasn't going to invite divine retribution upon all those who had taken part in my murder. Hopkins died two years after my death on 12 August 1647 in his home of Manningtree aged 27. He died of consumption and was quickly buried without ceremony in an unmarked grave, like mine, at the Church of St Mary at Mistley Heath. The tide had already begun to turn against him with people questioning his honesty and doubting his methods of torture against the vulnerable. He also published a book The Discovery of Witches in 1647 to defend his work and reputation. This publication influenced the methods used in the later Salem witch trials in Massachusetts where the extended Moulton family had settled.

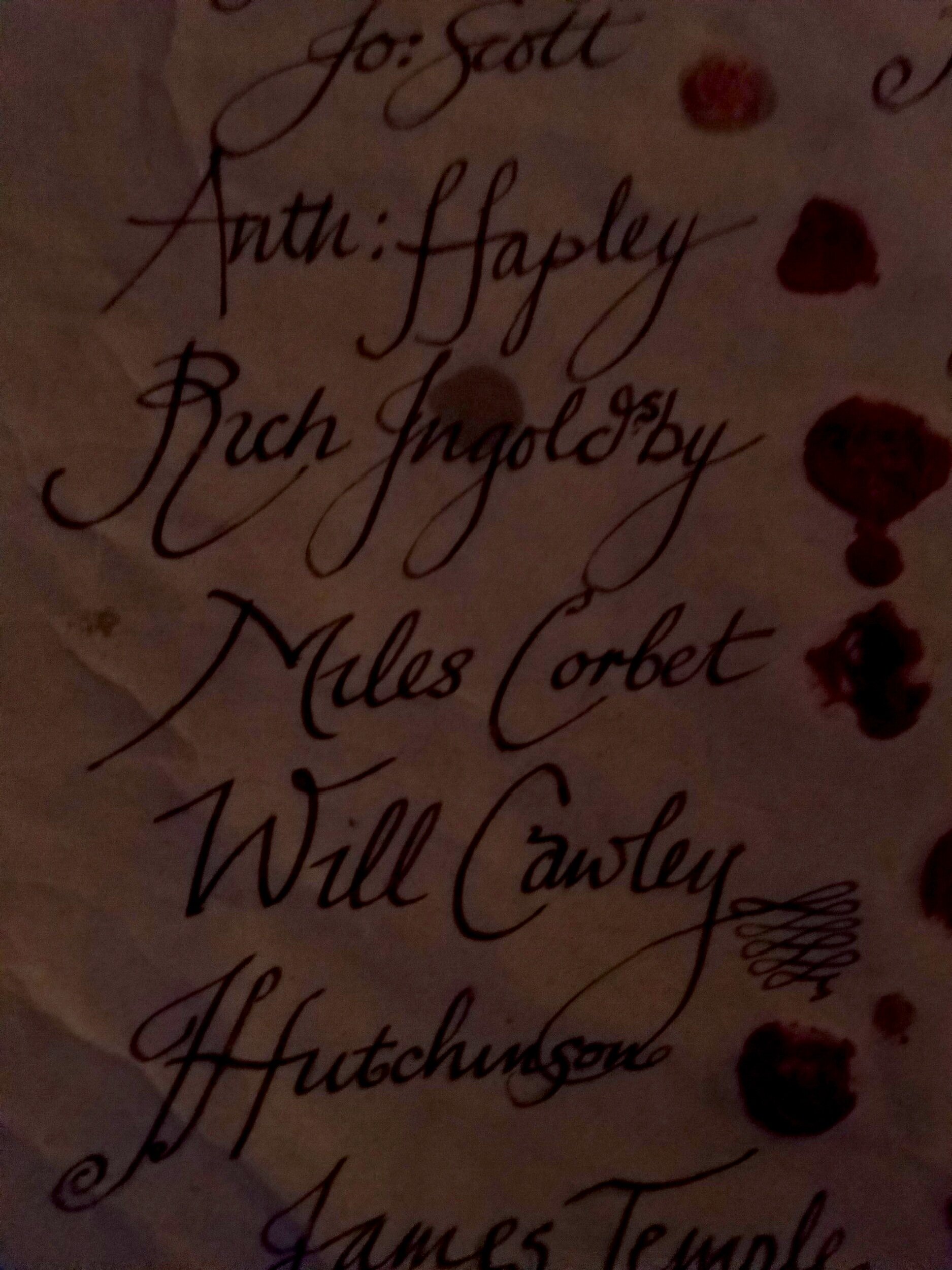

The town recorder Miles Corbet and Yarmouth town council

I was the 10th prisoner to be called to the trial hearing at the Yarmouth assizes held at the Tollhouse on 10 September 1645. All my accusers and interrogators were present, including Henry Moulton. It was Miles Corbet, chief magistrate, who had twice been MP for Yarmouth, and now town recorder who charged me with Malificia, the conjuring and entertaining of spirits, and of causing a life-threatening disease. He was a prominent, highly ambitious Independent puritan, who was friends with Minister Bridge and an ally of Oliver Cromwell. He was as keen as the rest of them to rid Yarmouth of people like me who, in their eyes, danced with the Devil. Miles was one of the most radical of Cromwell’s parliamentarians and chaired several parliamentary committees, most notably the committee for examinations where he gained a reputation for being a zealot inquisitor. He relished sending me to my death as much as he relished sending the King to his in 1648. Corbet was the last person to sign the death warrant for King Charles 1st, at that secret gathering of Parliamentarians in the grand, oak panelled Elizabethan house on the South Quay, the home of merchant John Carter. His portrait still hangs there today. I cursed Miles long and loud as I stood on the troll cart at the gallows and caught his black, pitiless eye.

It was with some satisfaction that I later attended his own execution on 16 April 1662 as a traitor for committing regicide. I could see every detail as I floated above the huge crowd gathered at Tyburn in London, to watch Corbet hung, drawn, and quartered. His guts spilling out like the herring fish I’d slice open on the beach to grill on the fire, and his limbs pulled from his body like the crabs’ legs I’d wrench off and crack to get to the sweet meat inside. His death was indeed worse than mine. English law stated that for the sentence of high treason:

“That you be drawn on a hurdle to the place of execution where you shall be hanged by the neck and being alive cut down, your privy members shall be cut off and your bowels taken out and burned before you, your head severed from your body and your body divided into four quarters to be disposed of at the King's pleasure."

I felt that a kind of karmic justice had been served.

The unnamed ones

There was a chorus of others whose names escape me now, that took me to my death. The jailor whose vile breath I could smell when he leered into the cell to throw me a slop bucket and dirty water to drink. The toll cart driver who took me on the long straight road to the gallows with most of the town following behind, pelting us with rotten food, and then plodding along with our bodies back to the churchyard. The hangman, with his rough gloved hands pulling the noose around my neck, and the gravedigger who was the very same man who dug the graves of Henry, Bridgit, John and Minister Brinsley. Within a few short years, most of those who killed me or witnessed my hanging ended up as my neighbours in the grounds of St Nicholas church. Death is indeed the great leveller.

Dear reader, you have come this far with me. You have heard my story which has so often been told and shaped by men, the very same that took my life. I’m lighter now for the telling.

I hope too that you can see, as I see, that the same patterns of violence have not gone away. Perhaps you might find a way to help a poor woman living on the edge. Don’t let society break her. Wouldn’t it be a terrible thing for the crimes that happened to me to carry on endlessly into the future?

Postscript: A prayer and pilgrimage for Elizabeth Bradwell, May to July 2021

In May this year, I started to walk with Elizabeth Bradwell. She was the name I received as part of the memorial spoon embroidery project, which I had taken part in last November. I already knew Yarmouth and had visited a few times over the years. I had taken an interest in the iconic Art Deco Iron Duke pub which the local community had been battling to save from destruction. Interestingly, it is at the end of the Jellicoe Road. My husband grew up in Gorleston, but neither of us had visited for a decade so I felt Elizabeth was nudging us both to return.

I felt my way into her story, researching online and piecing together the puzzle. There are conflicting dates in some of the histories, but the record that seemed to ring most true was the parish records of her burial date 29 September 1645. I figured that would also have probably been the day she was hung. During the research, I also found out that members of the Moulton family emigrated to the New England colonies at the same time my own puritan ancestor William Bradford was Governor of Plymouth, Massachusetts. The families may have even crossed paths over there. This brings an ancestral connection to this story in the same way that working with the story of Margaret Butter had in 2020.

Walking through Yarmouth in Old Lizzie’s footsteps was a powerful experience. More of the jigsaw puzzle of her story came together in person. It became a kind of pilgrimage. The finished embroidery contains sea-washed glass, found items and scavenged jewels from her hometown. The red fabric tangled with seaweed was washed up on Brighton beach. I felt that she wanted bright and shiny ornaments - the things that she could never afford in real life but might occasionally find washed up on the beach. The noose around her neck has become a beaded necklace coiled around the spoon. She is now cloaked in love and as free as the blackbird that she fed.

Old Lizzie was an edge-dweller, a beach comber and scavenger. A little bit like me .... maybe that's why she sought me out to help tell her story. Her familiar was a blackbird and everywhere I went in Yarmouth, a blackbird appeared.

I held a small memorial ceremony for her and the other women who are buried in the graveyard at St Nicholas. It felt like a strong release. I felt her anger and her grief. It was the weekend of the full moon in July - and to see it rise above the sea was a tremendous sight. Elizabeth Bradwell was coming home.

More information about the Medicine Spoon Memorial exhibition

Familiars – a poem written as part of the creative journey

References

East Anglia and the Hopkins Trials, 1645-1647: a County Guide

Anti-Puritanism and Urban Politics: Charles I and Great Yarmouth

Elizabeth Bradwell: Accused of Witchcraft and Executed in Great Yarmouth, 1645.

https://norfolkrecordofficeblogdotorg.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/dsc_0190-red.jpg

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A43992.0001.001/1:11?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

Brimstone | Witches in Early Modern England

The Discovery of Witches by Matthew Hopkins

The Discovery of Witches, by Matthew Hopkins THE DISCOVERY OF WITCHES

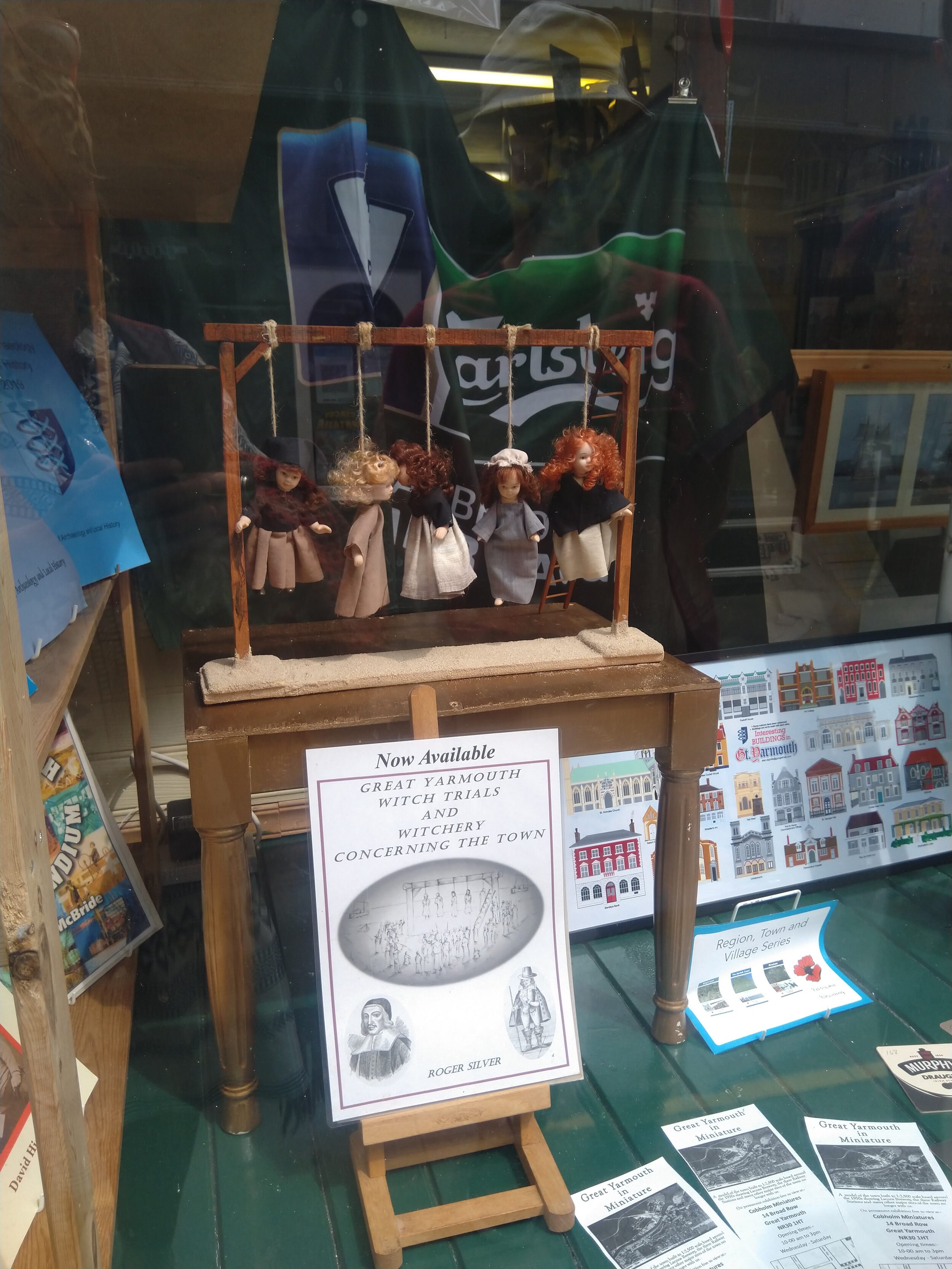

Great Yarmouth Witch Trials and Witchery Concerning the Town by Roger Silver